Pain is complicated, and what we feel is dependent on countless factors, including hormones. We’ve spoken before about how lifestyle factors, as well as psychology and medication can affect chronic pain.

Hyperthyroidism, where the body produces too much thyroid hormone, and hypothyroidism, where it doesn’t produce enough, are quite common conditions. Symptoms of either can be quite vague, so may be mistaken for something else. Although there are a lot of causes for these conditions, levels can be easily checked with a blood test.

Beyond the sometimes painful symptoms of hyperthyroidism, thyroid hormones appear to have an effect on pain processing. The exact relationship is unknown, but it seems that higher levels of the hormone are linked to pain from hot or cold stimuli.

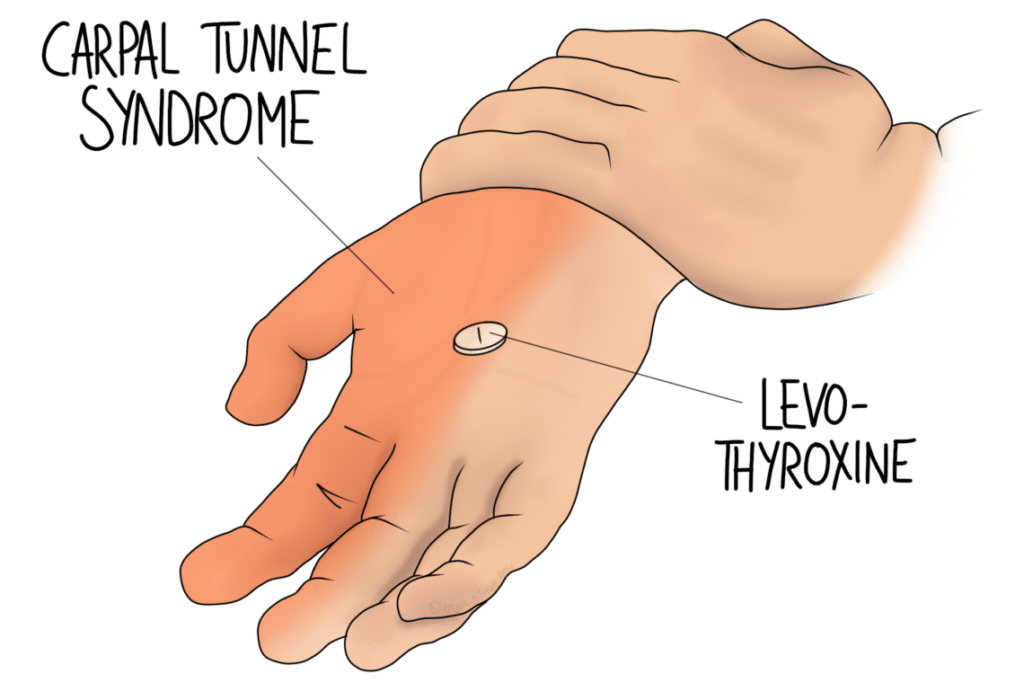

The NHS website notes that hypothyroidism is associated with a sensitivity to cold. It also mentions pins and needles and carpal tunnel syndrome. Hyperthyroidism can cause a sensitivity to heat.

There may also be a link between thyroid problems and incidence of fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia still remains largely unexplained, so to find associations with factors like hormone levels could be promising.

One study noted links between fibromyalgia and oestrogen changes in the menstrual cycle. The same study reported generally higher rates of pain with higher levels of oestrogen. This included artificial oestrogen, such as the combined contraceptive pill. HRT is another form of artificial hormone, and may be associated with an increase in jaw joint pain.

The same paper looked at the effects of testosterone. It showed that male mice recovered from sciatica quicker and more completely than the females. In human studies, the authors noted that women appear to suffer less neck and shoulder pain associated with desk work if their testosterone levels are higher. Both men and women also seemed less likely to have rheumatoid arthritis if their testosterone levels are high.

We need to bear in mind that it won’t be hormones alone that are responsible for these differences. The paper recognised that they are “thought to be one of the main mechanisms explaining sex differences in pain perception”, but other factors such including psychosocial ones will be at play.

With the knowledge that oestrogen has an effect on pain, it is not surprising that the menopause is associated with changes in pain sensitivity. Some women find that their headaches dissipate once they go through the menopause, whereas others might develop a migraine for the first time.

Another paper looked specifically at lower back pain and the menopause. Again, it recognised that pain is multifactorial, and that we need to consider biology, psychology, and social factors.

Stress perceptions, tension, anxiety, depression, and difficulty concentrating—increase throughout the transition, and have been found to be associated with an increase in back pain.

We need to recognise that the menopause is associated with increased pain for a number of reasons.

In a slightly different vein, pain may be higher post-menopause because injury is more likely. As oestrogen levels drop, so does collagen. Collagen’s role is to create strong, somewhat elastic tissue, such as cartilage. Less collagen is linked to higher levels of joint pain and cartilage degeneration. This is the process that also underpins osteoarthritis. Lower oestrogen is also a factor in the development of osteoporosis, which increases the likelihood of fractures.